A Vision for Healthcare AI in America

Share

By Sebastian Caliri & Finn Kennedy

In a few short years, AI has revolutionized software engineering, writing, and entertainment. Waymo’s autonomous fleet now captures over 27% of rideshare trips in San Francisco, and the number of self-driving Teslas on American streets is multiplying daily. Every aspect of life, even the DMV, seems to be changing rapidly with the introduction of AI.

But not the doctor’s office. The only thing changing there is your copayment, and not in the right direction. Is the technology ready? It has now been more than three years since humanity first turned sand and $0.005 cents worth of electrons into medical expertise capable of passing USMLE Step 1 – so the answer is yes. What gives?

Why should I care about healthcare AI?

“Why should I even care?” you reply. “I don’t want big tech oligarchs looking at my medical records anyway.”

First, the proliferation of excellent open source models means that AI can transform care without Sam Altman getting anywhere near your data. If that wasn’t enough, the robust patient protections embedded in HIPAA have existed since 1996 and are not going anywhere.

With that out of the way, maybe you should not care about healthcare AI if you are among the 1% wealthiest Americans that can afford concierge medicine. Things work fairly well for you already. But everyone else, especially the working class, has much to gain from a future where entrepreneurs, doctors, and technologists join forces to bring AI to our healthcare system.

1. Health insurance is making wage growth impossible

Do you know the owner of a small business? Call them up and ask how much more they are paying for health insurance in 2026 compared to 2025. They may not be able to accurately describe how much worse the benefits got as they became on average 7% more expensive, but they definitely know the 7% (or, anecdotally, 16%) is forcing tough budgetary decisions.

Consider that every employee at a firm earns a different wage, but that health insurance premiums are the same if you make $40,000 or $400,000. Consider also that at 7% growth, 2026 is a bad but not particularly anomalous year for insurance prices. Over time health insurance has become a bigger and bigger component of working class Americans’ pay; what was once 12% is now closer to 30% of total compensation.

.png)

While highly-paid individuals enjoy better salaries each year, every dollar that could go to working class wage growth is instead going to health insurance. Healthcare makes take-home pay stagnate or even lag behind inflation for a lot of Americans.

If the price of care drives premium growth, is there any technology you can think of that could impact those prices and therefore premiums? Are there any low cost substitutes to visiting the doctor you could imagine?

Marc Andreessen famously said “software is eating the world,” but for a lot of Americans the thing that is eating the world outside of working two jobs is healthcare costs. Healthcare AI is one of the few tools we have to funnel dollars from bloated insurance companies back to the pockets of blue collar workers.

2. It is a nuisance to seek and receive care

There have probably been times in your life when you’ve gone through great pains to schedule a doctor’s appointment. When the day arrives, you leave work, drive across the city to the office, sit in the waiting room for 20 minutes, only to answer four or five questions and hear “sounds good, keep on taking the medication”. You turn around to leave: “sir, with the deductible your payment will be $225. And before you head out, let me verify your insurance information…” Couldn’t this all have been a short phone call? And why did so little cost so much?

Routine tasks like post-hospitalization follow ups, medication adjustments, and chronic disease management are an excellent match for the capabilities AI has today. If we choose to make it possible, a quick chat with medical AI could replace low-complexity consultations and return missed hours of work (and income) to you. Instead of spending time on the phone with the UCSF scheduling office listening to hold music, you could be on the phone with your friends and loved ones.

This is to say nothing of ballooning wait times for a doctor’s appointment in the first place: 31 days in 2025, up from 21 days just a decade ago. At minimum, AI shortens the waiting window to discuss a concerning bump, rash, or medication that makes your heart race. In some cases accessing AI care immediately could be the difference between life and death.

.png)

Healthcare AI will not make your every healthcare experience a good one but it can give back hours of your time, resolve your problems more quickly when you have them, keep dollars in your wallet, and probably save you from a few white hairs along the way.

3. Liberty and dignity are at stake

There are many doctors who take great care to explain their thinking to patients and involve them meaningfully in decision making. The chances you have met one such doctor on a day they aren’t overscheduled is similar to the odds of winning the lottery. The inevitable result is an unequal dynamic where patients become accustomed to nonparticipation; medicine conspires to make patients spectators the second they set foot in a hospital ward.

Physicians have real expertise that non-physicians do not, but is it possible to imagine average Americans gaining an understanding of their health, the diseases they suffer, and the treatment options in front of them? Without a lot more physicians with a lot more time to spend educating and explaining, no. But with the broad diffusion of AI, yes.

One of the great possibilities of healthcare AI is to let ordinary Americans ask questions before an appointment starts and after it ends, receive answers in language they understand, and put them back in the driver’s seat in matters of their health.

4. Doctors deserve better

When only 37% of American physicians would recommend their own profession to their children, it is fair to say that something is rotten in the state of medicine. Is it prestige or pay? The former is in the eye of the beholder, but the latter can be assessed empirically. We know doctors are taking on perhaps $250,000 in debt to begin earning a salary in their thirties, but just how bad is it out there? If we think about medical education as investment and salaries as returns, some quick math suggests internal medicine is not much better than putting money in the stock market instead. Sadly, the stock market gets closer to winning every year.

.png)

This financial argument comes on top of well-known reports of physician burnout, fatigue with compliance, and frustrations with documentation requirements. Medicine takes some of the very best people in society, saddles them with years of debt, only to pay them salaries that don’t keep up with inflation while using software that barely works.

We need to find a way to pay physicians more. Paying physicians more requires growing productivity. The non-insulting way of doing this is not cramming more RVUs into doctors’ schedules but rather giving them an AI iron man suit to do more with less. New AI tools like scribes are already showing promise reducing the drudgery of button clicks and making the day-to-day grind a little less painful.

5. Millennials and Gen Z should have a shot at a good life

What do you call a system where early participants get far more out than they ever put in, where today’s payouts come straight from the pockets of new entrants, and where everything collapses the moment the base of contributors stops growing? A Ponzi scheme, right? Actually we just described Medicare. Another and somehow more charitable way to describe it would be a deeply unfair intergenerational transfer program from Gen Z and Millennials to Baby Boomers.

Baby Boomers enjoyed a system where there were four workers for every retiree to support; today that figure is well on its way to two workers per retiree. Those two workers are supporting Medicare not just with their taxes but also with the massive, growing federal debt that they will eventually need to pay down once the Boomers are long gone.

.png)

Healthcare AI is not going to entirely fix this problem. But no politician will win an election by proposing a cut to Medicare. The only solution at the intersection of “a big enough magnitude to matter” and “politically viable” is supporting the proliferation of AI to deflate costs and reduce utilization across all those currently on the consumption end of the roughly $1T we spend on Medicare. We don’t consider cutting scientific R&D or defense spending as options because we said “solution” not “way to induce the collapse of the last, best, free place on planet Earth.”

Healthcare AI is currently illegal

Whether the benefits of healthcare AI resonate with you or not, we will now return to the motivating question: why hasn’t AI done much for medicine yet?

The reason is that healthcare AI is currently banned de facto or de jure in the United States. By and large, healthcare AI can’t receive payments from insurance which makes it a losing economic prospect. Even if payments existed, all fifty states have medical practice acts that would likely prohibit AI from prescribing or diagnosing: offending H100s would be ripped out of us-east-1 and locked up in Manassas Regional Adult Detention Center for the illegal practice of medicine. At the federal level the Social Security Act puts further limitations on any healthcare practitioner not licensed by individual states. And so on: the restrictions are manyfold and located across a web of federal regulations, state law, and federal statute.

The silver lining is that we have chosen to keep AI out of healthcare but could build it if we wanted to. What would it look like to choose differently?

A vision for healthcare AI in America

“Healthcare AI” today can be more of a Rorschach test than a helpful and specific term. Everyone has opinions on it but the semantics are all over the place. Therefore we will start by defining our terms.

Healthcare AI refers to AI that supports care delivery (in e.g. hospitals, clinics, or at home) or is a substitute for those services. AI used for payer applications, pharmaceuticals, and biomedical research is outside our scope – but if it relates to doctoring it’s healthcare AI our book. Inspired by the six levels of self-driving that provide a common taxonomy for regulators and industry in autonomous vehicles, healthcare AI can similarly be stratified into four distinct levels:

Level 0: Administrative

AI that supports healthcare providers in back office or administrative tasks.

(E.g. Scheduling voice agents, AI scribes)

Level 1: Assistive

AI that assists clinicians but does not diagnose, treat, triage, or prescribe medications to patients.

(E.g. AI coaches, advocates, and navigators)

Level 2: Supervised Autonomous

AI that diagnoses, treats, triages, and/or prescribes medications to patients, with all or a subset of decisions monitored by a supervising clinician.

(E.g. AI medication management for chronic disease with physician oversight)

Level 3: Autonomous

AI that autonomously diagnoses, treats, triages, and/or prescribes medications to patients.

(E.g. Fully-autonomous AI emergency triage line)

Steps towards a golden age of American healthcare

Currently, solutions are being developed and deployed at level 0. In a few short years of existence, AI scribes like Commure, revenue cycle solutions like Candid, and patient scheduling agents like Hello Patient are already capturing over $1B in annual revenue. These administrative solutions are creating real value for healthcare providers. But they are not going to steer the Titanic that is American healthcare away from the iceberg.

Levels 1, 2, and 3 are the steps forward that can transform patient experience, costs, and ultimately health outcomes; these are also the types of healthcare AI that are variously banned today. It is important that each level is not only legally permissible but also investable to build and proliferate new AI systems.

We envision a future where we move from level 1 to level 3 through a series of policy changes that build upon each other and gradually widen the aperture for innovation in our healthcare system. Such an approach is more practical than a revolution, and also allows us to learn from each advance forward and accelerate or apply the brakes as we collectively see fit. Here is how it could work.

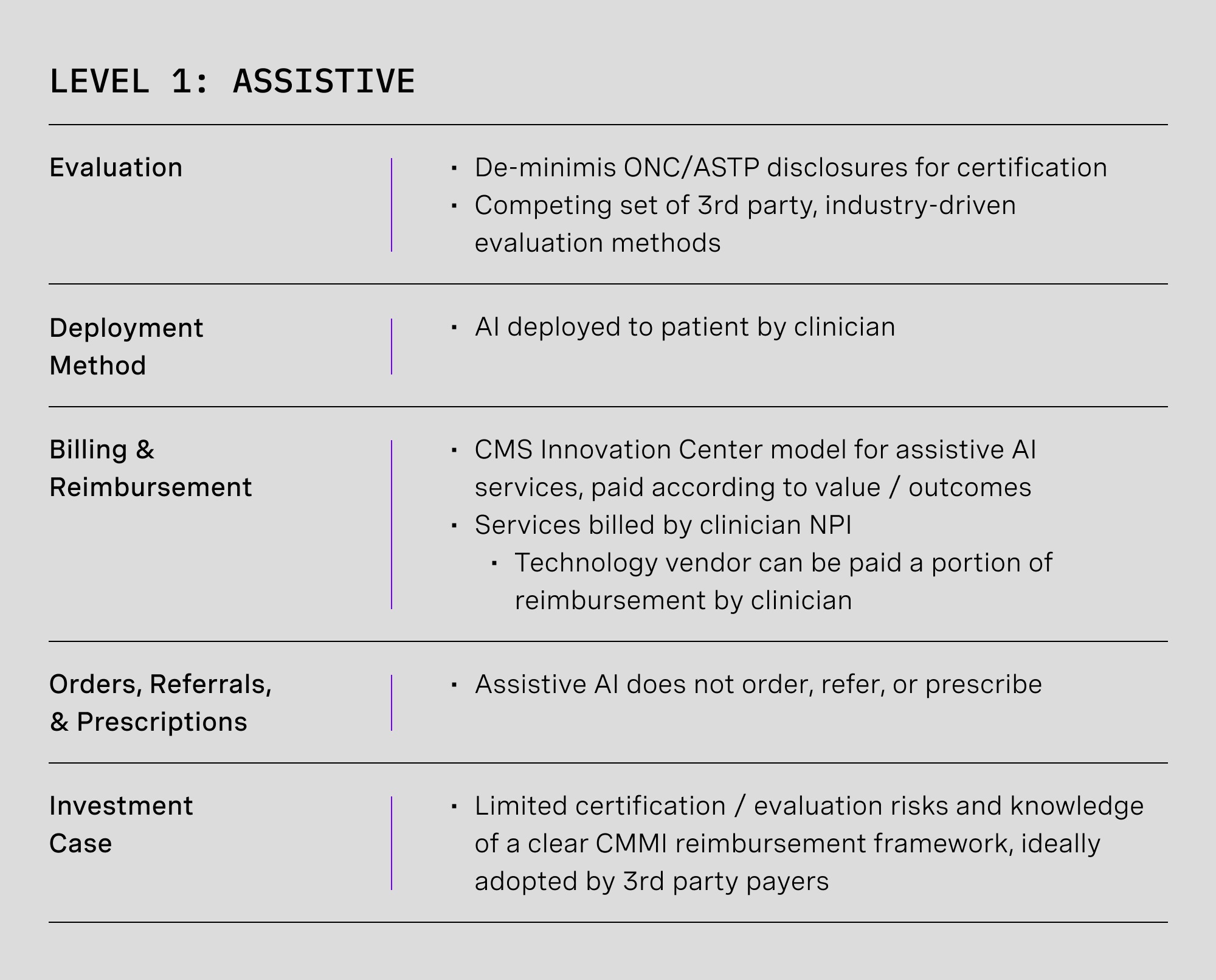

Level 1: Assistive

What is it?

Imagine being able to ask your doctor a question at any time of day via text, phone call, or video, and immediately getting a response. “Am I supposed to feel a bit nauseous with this new medication?” Or, “if I have to avoid potassium in my diet, remind me if I can still have a banana in the morning? What are some alternative ideas?” Or even, “watch me make this movement – should I keep wearing the knee brace or is it time to take it off? And can I do the hike with my friends on Sunday?”

Imagine no more: level 1 healthcare AI, assistive technology, could give you a personalized response to each of these based on your medical history, biometric data, and your doctor’s preferences. Level 1 cannot write a prescription or make a referral – those types of scenarios would still need escalation – but it could certainly make your life easier with advice, coaching, and education that wraps around the care you already receive.

How do we get there?

Level 1 healthcare AI exists today albeit under limited circumstances. Digital health companies like Omada, Superpower, and Citizen deploy assistive agents already as health coaches and advocates that help inform patients and supplement clinicians.

The main blocker for assistive AI care models is that no broadly billable CPT code matches the services they render. The companies mentioned above rely on alternatives like bespoke case rates, PMPM fees, or they just skip insurance reimbursement all together in favor of cash payments. Investors theoretically could fund more new businesses in the category but the uncertainty of ever being able to get paid by insurance is a massive impediment to capital efficiency and therefore investment activity.

There are also a few state issues to overcome as overzealous state legislatures have scrambled to “do something” about AI over the past year. And the HTI-1 Final Rule, published in 2024 under the Biden administration, could subject some of the assistive AI described here to questionable certification requirements as a de facto condition for market entry.

.png)

1.A. Implement pay-for-value reimbursement for assistive AI care models [CMMI]

Care models using assistive AI cannot currently receive insurance reimbursement because those services do not match any AMA-defined CPT codes. In fact, assistive AI could actually reduce provider revenues if applied towards services that bill time-based codes. Assistive AI needs private sector investment, and that investment will not be forthcoming if the only possible business model is charity.

Our previous writing on the topic of AI reimbursement describes a CMMI model for making value- or outcome-based payments to AI-enabled services that could result in durable codes, case rates, or monthly fees, readily adoptable by private payers. The more transparent the rate determination methodology, the stronger and clearer the signal to capital allocators and the more that resources can flow to the space.

Solving reimbursement takes level 1 healthcare AI from a paradigm of building technology followed by a multiyear lobbying effort to be paid by insurance companies to a world where valuable innovation can be very predictably rewarded.

1.B. Pre-empt heterogenous state restrictions and disclosure requirements [Federal Law]

Rather than supporting healthcare AI, many state governments have begun adding various restrictions to hobble it. Some examples of recent state laws include:

- California: mandates that every message that touches “patient clinical information” and was drafted by generative AI must carry a conspicuous AI notice at the top of emails, continuously in chat, and with clear instructions for how to reach a human clinician.

- Nevada: prohibits anything resembling AI mental-health care. If your product had a CBT coach, it is now disabled and if your marketing copy for your AI system implies “therapy” or “counseling” you face penalties.

- Texas: recently introduced two new laws that require patient disclosure when AI is used in healthcare, as well as a data localization rule that forbids physically offshoring medical records.

These heterogeneous restrictions imposed by individual states turn one nation-wide market into fifty distinct markets each with unique requirements for products to be introduced. This increases the cost of innovation for healthcare AI not just at level 1 but across all levels. If you need supporting evidence just compare the venture capital flowing into Medicare and employer solutions to the money going towards Medicaid innovation.

In July 2025, President Trump called for “one common-sense federal standard [for AI] that supersedes all states”. In the context of healthcare AI, federal law should clarify common disclosure and data storage requirements and prohibit wholesale bans on particular uses of AI to protect professional cartels. Other regulatory areas important to individual states (e.g. patient age verification) should not be dismissed but still ought to be preferentially addressed at the federal level.

1.C. Refocus HTI-1 certification on outcomes, not inputs [ASTP/ONC]

When you use ChatGPT, how often do you find yourself asking, “that was a great and useful response, but I wonder if the training dataset used Common Crawl from April 2025 or November 2024?”. These questions you might ask if you are gathering competitive intelligence on OpenAI’s state of the art models but not what users care about.

Under the Biden administration, ASTP/ONC promulgated the HTI-1 rule that would require some assistive AI systems to document their models’ training data provenance, update policies, evaluation methods and meet a long list of other compliance measures for official certification — in turn a de facto requirement for market entry. Compliance here encumbers small startups in favor of big tech and the large AI labs. Depending upon the details surfaced to EHR vendors and end users, there is also risk of trade secrets being exposed to competitors.

HTI-1’s predictive DSI requirements should be narrowed to disclosures on what providers and patients actually care about and what regulators should care about: how well they work in the real world, not how they were built.

Moreover, there should not be one single authority on level 1 system evaluation. HTI-1 should define de minimis “table stakes” disclosures, and a number of valid competing approaches should emerge bottom up to protect against regulatory capture.

Level 2: Supervised Autonomous

What is it?

Level 2 builds on level 1 by adding the ability to legally practice medicine: diagnosing, prescribing, and referring just like a doctor. Actually, more like a nurse practitioner or physician assistant: level 2 systems would be deployed to patients and overseen by a supervising clinician. All AI activities would be auditable and all or a flagged subset of medical decisions (e.g. unusual prescription changes, a decision flagged by AI for uncertainty, or anything flagged at the patient’s own request) could be subject to supervisor review before actioning.

Imagine you are hospitalized for congestive heart failure and prescribed a whole pharmacopeia of medications right before discharge. Some of the dosing would be right and some would need adjustment. Rather than coming back every few weeks (at a time no doubt incompatible with picking your son up from soccer) for changes, suffering from discomfort in the meantime, what if you used a home blood pressure cuff, AI chat, and mail order pharmacy to deal with it all on your own time? If you ever suspected something was off, or if AI suggested an usual recommendation, your doctor would get a notification to review the prescription first.

Young parents desperate for something to make life easier would also find relief in level 2 systems. Is it a viral infection or is it probably bacterial? Or did junior just somehow get a Lego into his ear? Forget about rushing to urgent care to find out. Your pediatrician has already given you access to an AI tool that looks at images of tongues, mouths, and little ears, and automatically writes a prescription for antibiotics if needed, and counsels other remedies if not.

How do we get there?

All autonomous AI is considered Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) by the FDA. The FDA label would determine what a level 2 solution can and can’t do – prescriptions, diagnoses, and so forth. We can think about a level 2 AI’s “scope of practice” as defined by its FDA approval.

The FDA evaluation process for AI systems is immature. Reviews often take too long, standards for approval are often too high (or in some cases, inappropriately low), and that only about 2% of approved SaMD has an authorized PCCP tells us that something is amiss with how we accommodate updates and upgrades.

Much like level 1, insurance reimbursement is also a barrier. Technologists will not build it if no reimbursement will come. At this stage, services will be billed under a supervising provider’s National Provider ID (NPI) number but assigning an NPI to the AI system will allow for prescribing and ordering and set the stage for insurance billing at level 3.

Meanwhile, certain state laws will need to be changed as level 2 autonomous agents come online. Each state has a number of “practice acts” that define types of healthcare practitioners and the services they are legally allowed to provide. Unsurprisingly, AI agents are not considered legal practitioners in any state.

.png)

.png)

2.A.1. Align FDA approval benchmarks with real world standards, not hypothetical ideals [FDA]

One problem with our FDA evaluation process for autonomous AI is that the performance bar is often set unreasonably high. LumineticsCore is an illustrative case study: the FDA required the tool to catch at least 85% of diabetic retinopathy cases, but studies show board-certified ophthalmologists land closer to 77% on the high end, and possibly as low as 33%. Our current approach is like making everyone who wants a driver’s license match Lewis Hamilton’s track record at Monaco: sure, you’d have fewer crashes, but almost no one would get a license and many would not even try.

AI should be measured against care people actually receive instead of subspecialists most patients never see. Although performance would be no worse than an average doctor visit, risk would be further mitigated by default escalation of low-confidence judgements from AI to supervising clinicians.

In the case of diabetic retinopathy only about half of eligible Medicare patients get screened at all owing to the accessibility and cost of services. We are making AI outperform the best of the best when the benefit of increasing access to average care in many cases dramatically outweighs the risks.

2.A.2. Reform PCCPs to allow continuous model improvement [FDA]

PCCPs don’t work in practice. PCCPs as constructed today must be highly specific at filing, and the AI research landscape is simply progressing too quickly to anticipate what changes may come in future years. It is also challenging to predict opportunities for systems to be extended to new populations or input data (e.g., adding CT when you start on X-ray; analyzing images captured with higher fidelity from newer machines) years before it is deployed in the wild.

FDA should revisit PCCPs to allow developers to make improvements while still minimizing risks. PCCPs should pre-approve a short list of upgrades that can launch with notice and live monitoring, like retraining on new data, like-for-like model swaps, and added inputs within the same modality. Sponsors should be able to expand plan scope by notification when risk does not increase, and full resubmissions should be reserved for changes that materially change the risk profile or add indications.

2.A.3. Require standardized postapproval monitoring [FDA, ASTP/ONC]

If the FDA approval bar is inappropriately high in some cases, it may actually be too low for SaMD on the 510(k) track. In a JAMA Health Forum review of about 950 510(k)-cleared AI devices, 60 were later recalled and many within one year of launching. These recalls were concentrated in devices that were approved by showing functional equivalence to other devices, but without submitting validation from actual use in the clinic.

Whether 510(k) approval should require some clinical validation or not is not a topic I will opine on, but what should be uncontroversial is the need for rigorous and standardized postapproval monitoring. It should be technically possible to implement reporting through ASTP/ONC EHR certification requirements. Such a rule not only serves the purpose of catching cases where recall is appropriate as early as possible, but can also serve as a foundation for evolving the PCCP, allowing sponsors to test updates at small scale to support more frequent and less burdensome improvements over time.

2.A.4 Create an FDA Center for AI (CAI) [FDA, HHS]

The FDA’s CDRH was created in 1982 to review medical devices and all kinds of radiation-emitting devices whether medical (e.g. x-rays, CT scanners) or non-medical (e.g. airport x-rays, consumer devices like TVs and monitors). This suite of responsibilities was already motley in 1982 and adding responsibility for cutting-edge AI is simply a bridge too far.

Evaluating healthcare AI will require a great deal of creativity and talent that simply does not match up with the expertise at CDRH. FDA should create a new Center for AI whose sole responsibility is the evaluation of level 2 and 3 healthcare AI. Perhaps there would be no need to even suggest items 2.A, B and C if we had started this way.

It makes logical sense to have a team of software experts working with software innovators instead of forcing a square peg into a round hole. This can be done with the authority already vested in the FDA commissioner and the HHS secretary.

2.B. Enact state Medical AI Practice Acts [State Law]

Building a functional level 2 system for medication titration or chronic disease management would be a miraculous achievement. But today it would be explicitly illegal in all 50 states because it contravenes state practice acts for AI to prescribe, treat, diagnose, and refer without an appropriate medical license.

The cleanest path forward would be for states to pass Medical AI Practice Acts that award a new class of medical licensure to FDA-approved healthcare AI. Approved SaMD could have a scope of practice aligned with its FDA label. An associated state Medical AI Board defined by the Practice Act can expand or contract scope as the label evolves, work with the FDA to monitor performance (in line with item 2.A.3.), and sanction AI companies that do not respond appropriately to inquiries and warning flags related to failure or degradation. States will ideally adopt uniform language for formation of Medical AI Boards to reduce the complexity of market entry for new models and create the strongest possible environment for spurring investment.

An alternative approach could be to bundle a federal AI Practice Act with the pre-emption of state disclosure laws described earlier (1.B.). A federal practice act would likely be seen as more intrusive on states’ rights than a national disclosure standard, but on the other hand would be a much faster path to making level 2 AI investable than fighting legislative battles in 50 distinct state capitals.

2.C. Implement provisional T-code payments to bridge FDA approval and reimbursement [CMS]

The FDA approval of a level 2 or 3 system may bless something as safe, but it may not provide CMS and other payers with the information required to determine a final reimbursement rate. But if we stack a costly and (possibly) unpredictable reimbursement timeline on top of a costly and (possibly) unpredictable FDA timeline, the uncertainty will make it hard to attract capital and talent for development.

After an FDA authorization, CMS should grant temporary T-codes with small provisional payments during this bridge period, billed using the NPI of the supervising clinician. This approach would be somewhat analogous to the New Technology Add-On Payment (NTAP) program for new devices. Reimbursement could be clawed back if prices were ultimately set lower than provisional rates or if a device’s approval was later revoked by the FDA.

Such a T-code system would kill two birds with one stone. It would provide cash flow for innovators, while also allowing CMS to gather evidence of value from real world deployment as an input to a reimbursement determination and code assignment.

2.D. Framework for autonomous AI coding and pricing determination [CMMI/CMS]

With a clear FDA process and provisional T codes to investigate real world performance, level 2 systems are off to the races. But how will reimbursement work in the long run and how will pricing be determined?

An approach could build upon the pathway described for assistive AI (1.A.) through (an) additional CMMI model(s) defined specifically for supervised autonomy. On pricing, others have written eloquently on autonomous AI reimbursement rates. How the details should work is a question for CMMI analysts and CMS actuaries. We only say that a clear process that results in a code, case rate, or other payment model that is easily billable by a supervising provider NPI and portable to private payers is what can facilitate development of the level 2 ecosystem.

2.E. Create NPIs for licensed AI providers [CMS]

FDA approval, state licensure, and insurance reimbursement still won’t quite unlock the potential of level 2 AI. There is one last administrative issue to resolve: transactions including e-prescriptions, referrals, and order placement require signing with a CMS-issued NPI as part of the data transmission standards defined by HIPAA.

CMS should create a new class of NPI for FDA-approved and licensed autonomous AI and require its use to be supported across all relevant senders and recipients of healthcare data: EHRs, e-prescribing, labs, payers, clearinghouses, etc. Ordering and referring rights are typically tagged to specific NPIs by payer systems and in this case could be inherited from the FDA label in the same way that state scope of practice can be.

While not used directly for billing at level 2, these AI system NPIs will unlock their usefulness beyond assistive systems and set the stage for direct billing at level 3. These AI NPIs will furthermore create a vector for assessing model behavior in the real world via inclusion in claims data.

Level 3: Autonomous

What is it?

Level 3 AI would have the ability to prescribe and diagnose, but unlike level 2 it would not need to be deployed by and directly monitored by a physician. Level 3 is in some sense a true “AI doctor”.

A world of level 3 autonomy looks like autonomous AI urgent care, available 24/7 without wait time, even in rural areas that lack other options to receive care. It looks like agents that persistently monitor biometrics across the medicine ward and catch signs of decompensation before a human possibly could, improving survival and reducing labor required to run a hospital. Perhaps there are behavioral or autoimmune conditions where AI can synthesize data and make better prescribing and dosing decisions than humans.

Routine and occasionally perfunctory work like refills for low risk drugs could be handled by AI too instead of wasting physician time. Is it really necessary to have all those doctors and nurses on the other side of the screen at Hims & Hers and Ro, clicking “yes” to prescribe your erectile dysfunction medication?

A human connection is essential to many aspects of medicine and it is unlikely that the most effective way to deploy level 3 systems will be wholesale substitution of your doctor in most cases. A better starting point to envision their role is asking “where are there places where autonomous systems can do things that humans alone cannot?” As well as, “where can human-computer symbiosis yield the strongest possible patient experience and patient outcomes?”

How do we get there?

Only a few policy changes are required to open the door to level 3 once level 2 is permissible. The biggest remaining issue is embedded in the Social Security Act, Title XVIII – the very source code for Medicare – namely, defining AI as a type of practitioner that can be eligible for reimbursement.

.png)

.png)

3.A. Expand state Medical AI Practice Acts [State Law]

Going from level 2 to level 3 requires an expanded scope of practice that can be assigned to AI, in particular changing requirements for supervision and oversight to permit full autonomy where indicated by the FDA. This would be enacted via changes to state Medical AI Practice Acts defined earlier (2.B.).

Uniformity of approach across states would once again create the best possible environment for investment – a single market is much better than fifty – but there is a case that states should be able to express different preferences. An FDA approval for level 3 autonomy could still be used in a supervised fashion (level 2) in some states without necessarily breaking the business model for innovators. Perhaps states may also want to license level 3 use for rural or underserved areas but only as a fall back when clinician supply cannot meet demand.

3.B. Amend the Social Security Act to allow Medicare payments to licensed AI [Federal Law]

Medicare was created in 1965 through amendments to the Social Security Act (SSA). Within the SSA various types of providers are enumerated as eligible for reimbursement by Medicare in section 1861. In 1965 this list included just licensed physicians; in 1977 Congress added physician assistants; in 1989 we added nurse practitioners. Today the list includes various types of social workers, therapists, and midwives. AI is not currently listed under section 1861. Even if CMS created a billing code for a level 3 autonomous service, it would be illegal for Medicare to make a payment directly to an AI company instead of a supervising physician.

Section 1861 of the SSA must be amended to allow Medicare to make payments to FDA-approved autonomous AI providers, using its own NPI, when acting within its label-defined scope of practice and licensed by the relevant state board.

Interestingly, Medicaid may not be subject to the same restrictions. Medicaid was also defined in 1965 as an amendment to the SSA and similarly enumerates what types of providers and services are eligible for payment in section 1905. The language leaves significantly more flexibility for interpretation by the HHS secretary to support payments to new types of licensed practitioners defined by individual states. It may be possible to run early pilots for level 3 autonomy in specific states to address high areas of need for Medicaid populations before seeking legislative support to serve and bill for Medicare beneficiaries.

The future of American healthcare will not be born without a fight

The one in six American adults that asks an AI chatbot medical questions each month can see a future that puts the world’s best specialists in your pocket. They can see a country that looks after working class and rural populations, dignifies Medicaid beneficiaries with access to care, takes the problem of physician burnout seriously, and gives Gen Z and Millennials hope for the future instead of saddling them with a soul-crushing amount of federal debt.

But powerful groups are working assiduously to make sure this future of abundance never comes to pass. Professional associations like the National Association of Social Workers, the cartel behind a ban of AI behavioral therapy in Illinois, will protect their monopoly at all costs. The American Medical Association similarly seeks to thwart AI systems while veiled behind a concern for safety. Big business hopes to capture healthcare AI regulation, crush any competition, and sequester all future profits for themselves.

Political factions are no better. Short-sighted socialists on the far left would rather sacrifice the future than allow private companies to profit from innovation. On the far right, a deep distrust of the technology industry has figures like Steve Bannon getting dangerously close to a call for Butlerian jihad.

We are on the side of the American people, patients, and physicians. We want safe and effective AI that makes healthcare accessible and excellent so that our country will flourish. Virtually all writing on healthcare AI is written by its critics and focused on the problems, risks, and restrictions that must be enacted. Almost none is focused on the benefits and the path to get there.

The American healthcare system causes all kinds of unnecessary suffering in obvious places like the hospital and in non-obvious places like your paycheck. AI is our best hope to alleviate that suffering. This plan has ambiguities and ideas that will be wrong when making contact with reality, but is our attempt to share a vision and a way to make that vision real.

Acknowledgements:

.png)

.png)