AI Doctors Won’t Work For Free

Share

Co-authored with Finn Kennedy

We are fortunate to live in an age where the cost of medical expertise is rapidly approaching zero. In just the past few months, OpenAI models were shown to outperform physicians on routine medical tasks and Microsoft demonstrated an ensemble of models with superhuman diagnostic capabilities. If you’ve used an LLM for a medical question yourself then you have likely understood the immense potential of this technology to make life better for patients, address chronic workforce shortages, and to make Americans healthier.

But if 8VC portfolio company Cognition is already automating parts of software development today, Candid is taking labor out of revenue cycle management, and agents are showing up everywhere from law to customer service to recruiting – your doctor still isn’t deploying an AI agent to handle your questions or medication adjustments. We recently wrote about how a wave of AI services companies are reshaping industries by automating knowledge work previously thought to demand human judgment. Why not healthcare?

A common refrain is that safety, quality, accuracy are the primary barriers to overcome but that perception is wrong. It is our payments system that is the bigger problem. Most payments in healthcare flow not from individual consumers but health insurance companies. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sets the rules for how all types of health insurance pays hospitals, doctors, and other types of clinicians. But it has not clearly defined a way to pay for AI that assists doctors or that autonomously renders a service.

The bots won’t work for free. To get AI into care delivery, CMS needs to create payment rails for AI-native healthcare too.

How do payments to clinicians work today?

CMS relies on a set of over 10,000 five-digit Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that define all of the billable services clinicians can offer. For instance 36415 is a routine venipuncture; 90471 refers to vaccine administration; and other codes exist for consultations, imaging studies, surgeries, and more. The CPT codeset is maintained by the CPT Editorial Panel within the American Medical Association (AMA) which meets three times a year to consider new codes and definition changes.

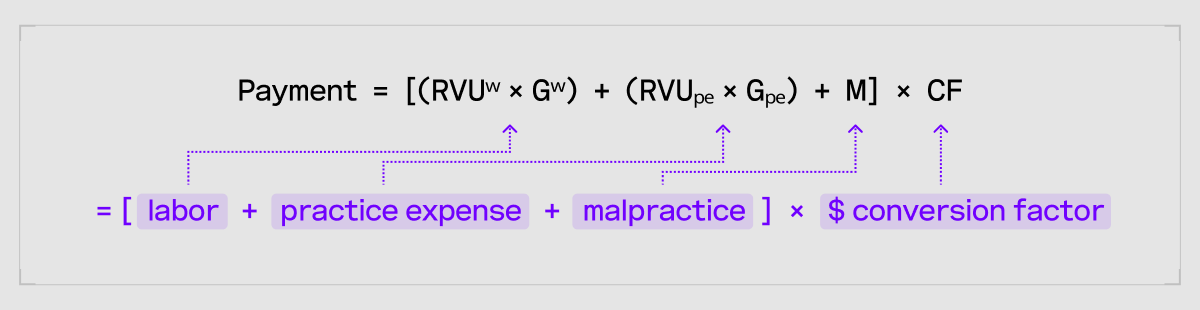

What do we pay for each code? Reimbursement rates are derived from the AMA’s RVS Update Committee (“RUC”), which defines the amount and complexity of labor as well as cost of equipment and supplies required to complete a coded service. These factors are multiplied by a dollar value conversion factor to arrive at Medicare prices for a code.

These codes and prices are not just used by Medicare. Every form of private health insurance in the United States also uses the same code set for defining billable services and inherits the Medicare prices as the basis for their own rates.

The RUC defines key terms that determine payment for a given CPT: the amount and complexity of labor used (RVUW), practice expenses like supplies and equipment required for a service (RVUPE), and malpractice expenses. These terms are each modified by a geographic factor (GW and GPE) that account for local variations in cost. The terms are summed and multiplied by the conversion factor (CF), set by Congress and CMS to yield a dollar value reimbursement figure for the CPT.

This AMA-dominated process is controversial even without considering the new challenges posed by AI-native services. Labor complexity is subjective and can be manipulated by well-resourced specialist groups at the expense of primary and preventative care – to say nothing of the roughly $300 million in annual fees the AMA earns licensing CPT to CMS, commercial insurers, and EHR vendors. The AMA’s influence on the structure of American healthcare is not a new story, Paul Starr won a Pulitzer in 1984 for The Social Transformation of American Medicine and we won’t attempt to retell it here.

Pertinent to our discussion is simply that CPT was built for an older, 20th century model of healthcare: a physician, in a room, performing a discrete intervention. That’s the type of service it knows how to taxonomize and price. But the advent of AI provides an opportunity to change the balance of work between human clinicians and computers. Because agents are infinitely scalable, care can be continuous or ad hoc. It can be made available at any time and anywhere and its utility is not limited by human labor input. And we have made it nearly impossible for health insurance to pay for any of it.

If we try to boil it down to essentials, the primary barriers posed by our CPT rails are:

- Code definition clock speed: The CPT Editorial Panel meets only three times a year but new types of AI-native services are born daily. What worked for a world where there was little innovation in care delivery simply cannot accommodate the cambrian explosion of possibility happening today. We need a fast-moving and high throughput alternative. And while the CPT Editorial Board is composed of medical experts, today technologists need a seat at the table too.

- Episodic emphasis: CPT codes generally align with discrete time- and space-delimited episodes of care. But AI agents are infinitely scalable and can be engaged any time and anywhere on a continuous or ad hoc basis – either alone or with the periodic involvement of a clinician. Episodic payments defined by CPTs make less sense than something more akin to a subscription model in many cases.

- Labor-based pricing: A pricing model tied to human labor penalizes AI-powered care delivery that explicitly reduces human labor required for a particular service. Should payment be reduced when patients get the same result with less labor? Some services also might have an agent engaging a patient and only escalate to a clinician as needed. How do we price a service with a highly variable labor component?

- Indifference to quality and convenience: This pricing model also makes no distinctions based on quality and does not reward services that deliver the strongest patient experience. This is a problem even without AI but still deserves thought in a moment when our payments system is up for discussion.

In line with the above drawbacks, here are a few examples of valuable AI innovation whose proliferation has been slowed down in some way by our payment rails:

- Digital Diagnostics’ LumineticsCore is an AI system that conducts diabetic retinopathy screening using an autonomous AI model. The FDA approved the model in 2018 but it took three years of discussion from that point to assign a billing code and determine an appropriate framework for pricing the code.

- Nabi uses an agent to support patients with eating disorders on a day-to-day basis while periodically escalating to a dietitian or doctor as needed. Today only the interactions with clinicians are billable, not the AI touchpoints. Additionally, because clinician visits are billable in 15 minute increments, clinician time can’t be used flexibly for short ad hoc or asynchronous interactions without cannibalizing billable encounters.

- Companies like Cadence offer remote patient monitoring (RPM) services – analyzing data from connected blood pressure cuffs, scales, etc, and periodically engaging with patients to manage chronic disease. Today, some RPM codes exist (e.g. 99454, 99457) but the reimbursement value is tied to human labor, penalizing efficiency gains from AI. If AI can reduce the work a clinician has to do to analyze trends and help a patient stay healthy, should RPM providers be penalized with lower rates? Or if AI can help clinicians address more complex cases, should there not be some reward?

The status quo hasn’t ground AI in care delivery to a halt. Each of the above examples have been able to access some CPT-based reimbursement. But it is hard to honestly conclude our payments system is configured to support AI-native healthcare. New AI-native services that safely deliver strong patient outcomes should be able to flourish and reach those who would most benefit.

To advance AI-native healthcare, we must create a better way to access insurance dollars. How?

Reforming the CPT process is one idea. We recognize the efforts of the AMA’s Digital Medicine Payment Advisory Group to adapt the existing RVU reimbursement framework to more fairly value AI-based services. While supportive, it is a bit like fitting a square peg in a round hole. We remain cautious given the pace of AI innovation and the imperative of moving quickly. CMS could also perhaps build a process around G codes, but we have similar concerns about that pathway.

We could fairly describe private payers as another escape valve. Companies like Hinge Health have successfully grown their AI-native services through negotiated carve outs from employers and other private health plans that side step CPTs altogether. But this process is simply too slow, it largely excludes our Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries from coverage, and most damningly it favors insiders over insurgents. Healthcare AI upstarts shouldn’t have to hire legions of consultants and advisors to lobby insurance executives just to get paid for the value they create. A better route exists.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the CMS Innovation Center (CMMI) “to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures… while preserving or enhancing quality of care.” There is no better use of that mandate than building a new payment rail for AI-driven care. In fact, the current CMMI Director Abe Sutton has spoken of the potential for AI to “massively increase our supply of healthcare” and the importance of defining reimbursement pathways for AI.

CMMI should launch reimbursement pilots explicitly designed for AI-native care. Some guiding principles for these pilots could include:

- Transparent and rapid coverage decisions: Today, new services are subject to slow, opaque decision-making processes if they are considered at all for CPTs or by private payers. A new application process should be created for AI-native services with clear eligibility criteria. Roll out the red carpet to healthcare newcomers and veterans alike. Offer transparent evaluation criteria and rapid timelines for making decisions.

- Real world data-based evaluation: For AI-native services that pass an eligibility bar set by CMMI, services could be tested in the real world. Requiring periodic T code billing would allow CMS to track where these new services are used and on which patients, to later determine impact on total cost of care, utilization, accessibility, and / or patient experience. Optionally, CMMI could tie modest temporary reimbursement to T code claims to defray cost and help ensure good record keeping. This would in some ways be analogous to the TCET pathway for medical devices.

- Pricing on value: After an evaluation period, durable reimbursement could be set at a rate that comfortably delivers strong ROI to government entitlement programs. Reimbursement could come in the form of episodes, case rates, or flat monthly or annual fees.

- Patient choice and competition: CMMI could optionally allow AI-native service providers to adjust patient co-payments relatively lower or higher. If for example two services deliver about the same value to CMS and are reimbursed at the same rate, patients could elect to pay a higher price for convenience or advanced features, or select a lower cost option according to their preferences.

This framework is necessarily incomplete in many dimensions. Evaluation criteria and determining ROI to government programs is not a simple assessment to make. But if AI is doing most of the work for a given service and the marginal cost of AI approaches zero, it should be possible to land on rates that both earn AI-native services sufficient margin and give government comfort that a service will not increase costs. Private payers also would need to adopt the approved AI services and reimbursement approaches identified by CMMI. And CMMI would need to constrain the number of applicants and services considered for evaluation given limited resources.

The safety and accuracy question referenced earlier still must be resolved, although we see this primarily as a political decision on acceptable levels of risk considered against reward. The number of mistakes human clinicians make is not zero. Even established medical practices sometimes contradict evidence of safety and efficacy as Dr. Vinay Prasad wrote in 2015’s Ending Medical Reversal. And if AI can increase access, we ought to credit technology against the counterfactual of a patient languishing without any care at all.

—

As we have written previously, American healthcare is barreling towards a fiscal reckoning. If we don’t address the growing costs of healthcare entitlements, Washington will soon face more and more impossible tradeoffs: cutting off care for millions, gutting defense, neglecting border security, or imposing punishing tax hikes.

AI is our best bet at getting more for less. And if we can open the door for our best medical experts and technologists to innovate by establishing sensible payment rails for AI-enabled care, we can apply our world-beating American creativity to transform care delivery in the same way we are revolutionizing every other part of the economy.

Acknowledgments

Chris Altchek

John Bertrand

Dr. David Brailer

Meryl Holt

Neal Khosla

Dr. Robert Nordgren

.png)

.png)